Why antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health crisis

Part 1: The threat from antimicrobial resistance and what we can do about it.

“An acute risk in so far as it poses continuous challenges that erode our economy, community, way of life, and/or national security”.

At a time of growing geopolitical instability, the above statement could apply to any manner of physical or digital threats: from an aggressive, expansionist Russia to the misuse of artificial intelligence.

The subject in question, however, is the much less talked about threat (in mainstream media circles at least) to public health caused by antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – the phenomenon whereby organisms that cause infection evolve in ways to survive treatment from existing medicines. In the first of two parts, we explore why AMR is a growing public health crisis before detailing the work that’s happening to keep the food chain – and the public – safe.

Risk recognition

Each year AMR is estimated to cause almost 1.3 million deaths globally and 7,600 deaths in the UK alone.

The risk from AMR has become a fixture of the national risk registers of both Ireland and the UK for the best part of a decade. The above statement comes from the latest UK national risk register, for 2023, which describes how AMR has the potential to render critical antibiotics ineffective and so exacerbate the risk that infectious diseases lead to higher deaths.

Each year AMR is estimated to cause almost 1.3 million deaths globally and 7,600 deaths in the UK alone. The impacts of leaving it unchecked are huge, not only through lives lost but our ability to undertake modern medicine, for food sustainability and security, and for environmental wellbeing and socio-economic development.

In 2014, concern about AMR reached such a level that the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, commissioned an independent review on AMR, chaired by the economist Lord Gus O’Neill. His report, published in 2016, made ten recommendations to address the problem, including improved hygiene and infection prevention, reduction of unnecessary use of antimicrobials, and improvement of global surveillance of drug resistance and antimicrobial consumption in humans and animals.

Since then, many national governments and institutions like the World Health Organisation have made tackling AMR a priority, mostly through the adoption of a ‘One Health’ approach that integrates human health and social care, animal health, agriculture, food production and the environment. Ireland is now well into its second action plan aimed at addressing the threat from AMR and will launch its third plan by the end of this year.

“Since 2017 [when the first action plan was launched) I think it's fair to say that it has gained considerable momentum at government level,” says Caroline Garvan, Senior Superintending Veterinary Inspector at the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine.

The UK similarly has a long-term vision for tackling AMR through a series of 5-year national action plans, which aim to bring together organisations across government to contain, control and mitigate AMR by 2040. The first action plan ran from 2019 to 2024 and the second, which will run until 2029, kicked off last year.

Food chain reaction

The over-prescription of antibiotics to treat human illness is one reason for the growth of AMR but another key factor is the inappropriate use of antibiotics for disease prevention and treatment in animals.

Like people, animals carry bacteria in their guts. This includes AMR bacteria, which can get into food in several ways.

When animals are slaughtered and processed for food, AMR bacteria can contaminate meat or other animal products. Animal faeces can contain resistant bacteria which escapes into the surrounding environment, while fruits and vegetables can become contaminated through contact with soil, water or fertiliser that contains animal faeces. People can also get intestinal infections, including AMR infections, by handling or eating contaminated food, handling raw pet food, or coming into contact with untreated or uncomposted animal faeces.

Our knowledge of the link between AMR and food is growing all the time as scientists learn more about how resistance arises and how resistant bacteria survive and are transmitted through the food chain – from people to animals as well as animals to people, both directly and through the environment.

Meat link

One potential source of transmission is via consumption of meat products.

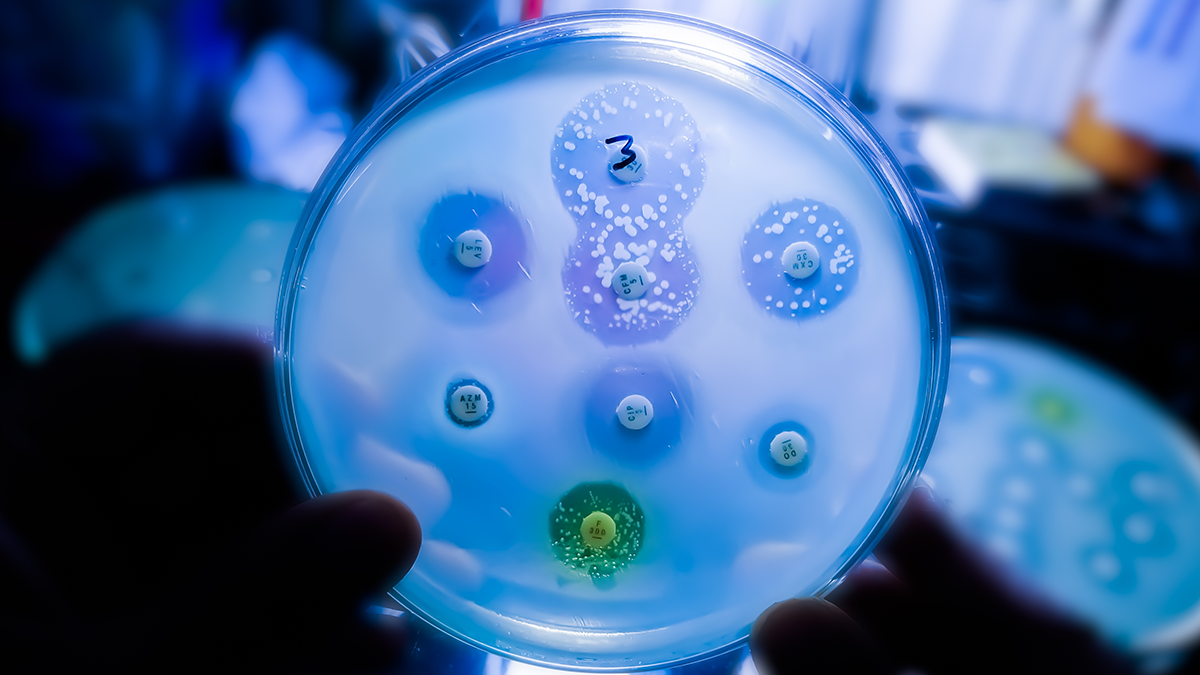

In May 2022, the UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) commissioned a survey to assess the amount of AMR in bacteria in fresh pork mince and fresh and frozen chicken on sale in shops in the UK. The aim was to help establish a baseline of the occurrence, types and levels of AMR in bacteria found in such products, which in turn could inform future surveillance on AMR in these foods.

The survey involved testing Campylobacter in chicken samples and Salmonella in pork mince samples for the occurrence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. It also looked for AMR in other bacteria in both types of meat including Enterococci, Klebsiella and Escherichia coli.

Antimicrobial resistance was detected in a proportion of all the types of bacteria examined, with resistance to the most clinically important drugs generally appearing to be more prevalent in chicken isolates than pork.

Regulators insist the presence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in food products doesn’t of itself give cause for alarm. "The risk of acquiring AMR related infection through food is very low providing that good hygiene and cooking practices are followed,” points out Kathryn Callaghan, Microbiological Risk Assessment lead at the FSA.

Callaghan also notes it is the responsibility of food businesses to make sure food is safe: “By law, retailers and manufacturers in the UK must regularly sample and test their products to ensure food safety.”

Linking illness with AMR

One of the main difficulties in diagnosing and treating AMR-related illnesses is that the issue straddles multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at various levels of society. That makes piecing together the data linking foodborne illness outbreaks to AMR challenging.

In the UK, for example, the FSA records data on foodborne illness outbreaks, including AMR data when available, to which it is alerted by a public health or local authority. Key information is recorded throughout the outbreak investigation, including whether the outbreak is linked to AMR. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) will usually take the lead in co-ordinating the government response to UK-wide outbreaks, with the FSA leading on food chain investigations.

AMR is one of the parameters routinely monitored by UKHSA and used for its risk assessments and outbreak response (the EU also routinely runs surveillance programmes to monitor AMR in humans and animals). Each year, it publishes the results of a surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance in England including critical antibiotic resistance in foodborne bacteria.

For the latest year covering 2023, mobile resistance genes conferring resistance to colistin – a critical human medicine for treating life threatening infections – were found in a small number of Salmonella spp. and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) isolates, while tetracycline resistance was also found in a small number of Salmonella spp. Isolates.

In its analysis, UKHSA noted that most foodborne bacteria cause self-limiting gastroenteritis that does not need to be treated with antibiotics and that various treatment options remain available, albeit the impact of resistant infections may be particularly significant for individuals that are immunocompromised and for other vulnerable groups.

It also restated the FSA’s advice that thorough cooking of food to piping hot temperatures and maintaining good kitchen hygiene is one way of reducing the acquisition of foodborne infections.

Falling drug use

Stakeholders are working across the food supply chain to combat the threat from AMR before food reaches the end consumer.

“It’s not really an animal problem, it's a people problem. People give the antibiotics to their animals, or they take them themselves.”

-- Caroline Garvan, Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine

It is widely accepted that driving down inappropriate use of antibiotics, including within animal agriculture, is a key means by which to slow the development of antibiotic resistance. Data for 2022 contained in the latest UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance Report shows a 59% decrease in UK-wide sales of veterinary antibiotics intended for food-producing animals since 2014, while sales of the highest priority critically important antibiotics have fallen by 81% during the same period.

Garvan notes that in Ireland too there has been a significant reduction of around 28% in sales of antibiotics since 2020, driven in part by an action plan which is bought into by all stakeholders including veterinarians and farmers.

“It’s not really an animal problem, it's a people problem,” she says. “People give the antibiotics to their animals, or they take them themselves.”

Yet despite sustained progress in reducing antibiotic use in animals over several years, experts say more still needs to be done to tackle the threat from AMR. In an evaluation of the UK’s first national action plan (2013-18) by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the organisation’s Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit (PIRU) concluded, among other things, that improved data to inform AMR policy development is needed including on the contribution of the food chain to AMR rates.

Plugging that data gap was a key focus of the UK’s Pathogen Surveillance in Agriculture, Food and Environment (PATH-SAFE) programme. Over the past four years, the cross-government and UK-wide programme has been piloting the development of a national AMR surveillance network to improve the detection and tracking of foodborne human pathogens and associated AMR through the whole agri-food system from farm-to-fork.

In a 2023 FSA blog post, Callaghan, along with her colleague Dr Erica Kintz, wrote of PATH-SAFE: “If we can find the sources of AMR infections that are commonly spread through food and animals, we can prevent onward transmission by promoting safe food handling and safe contact with animals.”

In Part 2, we will explore in depth how regulators and businesses are working together to combat the spread of AMR and keep the public safe. And we’ll consider how AMR is being treated both through conventional and alternative therapies.